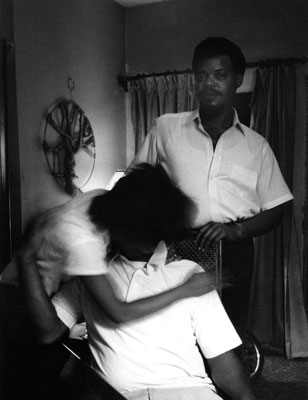

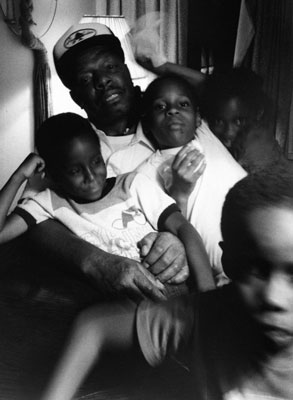

Family Pictures and Stories, 1981–1982

Carie Mae Weems’ Retrospective begins on her very roots, a cluster of photos entitled, “Family Pictures and Stories (1978–84)”. There was something endearing in the photo I became fixated on at the very first series that I encountered. The photo captured an elderly black man sitting on a chair while a younger black fellow was holding the top brace of the chair on the right from the back. They both looked at the camera with a sense of familiarity with the photographer and both posed with comfort from possibly knowing each other for an extensive amount of time. Both men were neither smiling nor were in any discomfort. Instead, the softness of their face indicates that they are possibly inside the very home that they shared together. While the photo that captured a tender moment between them seems to bring about a sense of gentleness, love, and familiarity, the artist weaves a narrative to this piece that brings a gut-wrenching truth confined with the characters in the photograph. The narrative of the piece entitled, Dad and Son-Son, shared a disturbing fact about a shared experience between the two men; the father and son truly did love one another but during one instance after the two men drank heavily, both whipped out pistols and fired at one another. After this surge of violence immediately came the tenderness of the son’s crying and pleading, “Daddy, daddy, I’m sorry.”

"It was clear, I was not Manet's type Picasso...who had a way with women... only used me and Duchamp never even considered me"

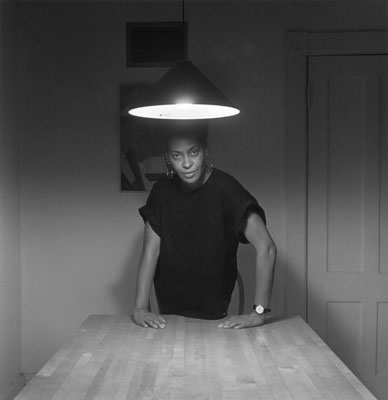

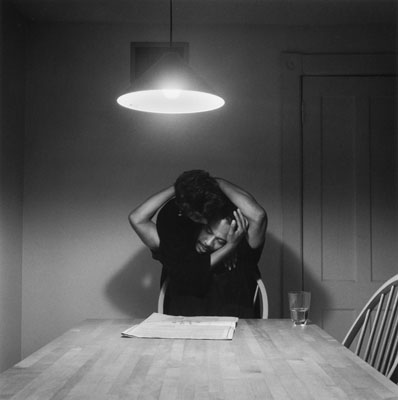

The piece encapsulates Carrie Mae Weems’ body of work in to two words: endearing and disturbing. Her entire work swerves Guggenheim’s walls like tracing a woman’s curves and the narratives that envelopes it pricks the heart with every step. It forces you to stare and then once you bite and glance at it, it continues to ask why you were looking. Like a feisty woman baring herself out it suddenly darts at you for looking and prodding. In her work, “Not Manet's Type, 1997”, we find a woman contemplating on the things that society deems that a woman should look through a series of photos. The photos depict a woman alone in the room getting naked and initially almost reluctant of her body but ends with the last photo of a woman lying down on the bed, naked and without a care in the world. Like its narrative that seems to ask the question to what our society deems as beautiful, most of her work constantly asks the things that are seemingly normal to you and questions the things that you find beautiful, funny, acceptable, and erotic.

Carrie Mae Weems took upon the responsibility of taking beautiful photographs of unapologetic truth combined with vivid narratives about being black to bring about positive change. Weems’ explains, “my responsibility as an artist is to work, to sing for my supper, to make art, beautiful and powerful, that adds and reveals; to beautify the mess of a messy world, to heal the sick and feed the helpless; to shout bravely from the roof-tops and storm barricaded doors and voice the specifics of our historic moment.”

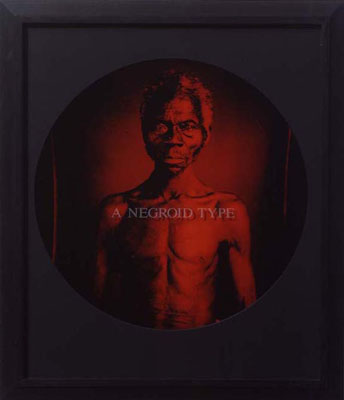

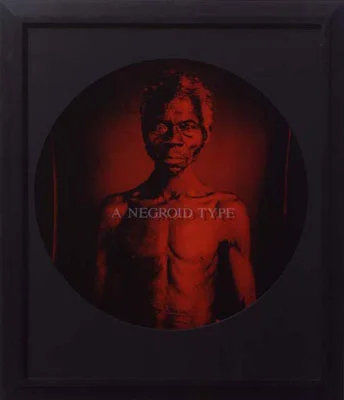

From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried, 1995–1996

"A Negroid Type"

"You Became Playmate to the Patriarch"

"Black and tanned Your Whipped Wind of Change Howled Low Blowing Itself-Ha-Smack Into the Middle of Ellington's Orchestra Billie Heard it too & Cried Strange Fruit Trees"

The entirety of the exhibit throbs like a heartbeat. There are moments of warmth and gentleness that thumps a placid pacing and then braces to the rawness and painfulness of its sharp narrative and then it brings you to moments when your heart stops, pauses, then drops deep within your core burning a fiery hole.

In 1995, Weems was commissioned to investigate historical photo-images of blacks from the Getty Museum. This led her to create From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried a series of photographs integrated with texts that bring to life thoughts, questions, and experiences of the black community from these photos. The images were toned in red and begin with photos of African men and women then moves along to photographs of African slaves dressed in western clothing and even contained a disturbing image of a slave with its back torn from whipping. The images alone seemed more of an anthropological collection of a disturbing past but Weems paired it with the most emotional color – red and added gut wrenching narrative of what had become of the people that were brought from Africa to the West. The photos coupled with the texts were strong, sharp like a piercing blade, and it felt like walking on hot lead as the viewer progresses through the series.

Carrie Mae Weems’ work is a feast and a delight to one’s eyes. She captures beauty in the grit and truth and yet the narratives scratches, burns, stabs, and boils me. Its beauty forces me to look and the words like a sharp tongue shouts the reality to me and questions me. It was as if I saw a beautiful woman and her words made me purge and she had me swallow the searing vomit in my mouth.